When confronted with the task of comparing two fundamentally disparate objects, cliché-wielding literary hacks frequently assert the two objects are “as different as night and day.” It’s a quick and effective means to punctuate one’s argument that each object is utterly unique and should thus be considered on its own merits.

Being somewhat of a literary hack myself, I briefly considered taking the banal route and invoking the “night and day” cliché for this article — except that this article is actually about the differences between night and day. To wield the cliché here would be like those enigmatic dictionary writers who define “zumbaloofer” as “one who zumbaloofs,” while simultaneously defining “zumbaloof” as “the actions of a zumbaloofer.” Pointless.

So what are the differences between night and day? What distinguishes one from the other?

The most obvious answer, of course, is light. Specifically, day has an abundance of it. Night? Not so much. For those of us who are photographically inclined, this makes the night somewhat of an adversary. It’s why photographers are forever employing various tactical weapons against that adversary: flood lights, flash guns, fast lenses, long shutter speeds or low-noise/high-speed sensors. Each of these solutions exists for a single reason — to bring more light onto our camera’s imaging plane.

This is all well and good, if you’re trying to take night photos that emulate those you take during the day. But there is more to distinguish night from day than the quantity of light. Much more.

If we consider daytime the equivalent of a photographic positive, then night must surely be its negative. During the day, the sky is often the brightest thing in the photograph; at night, it’s the darkest. During the day, a building’s façade appears bright and its interior dark. At night, it’s the opposite — the secret contents from within are projected through darkened walls into the dim night air.

When contrasting day with night, this positive/negative comparison extends beyond the literary and into metaphor. There is a different energy at night, a different rhythm. People’s moods change. Their perceptions alter. Their needs metamorphose. Their priorities shift.

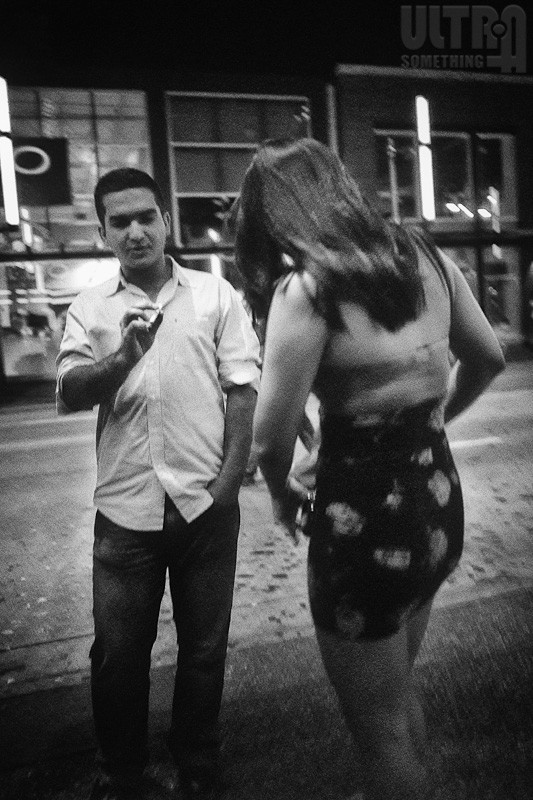

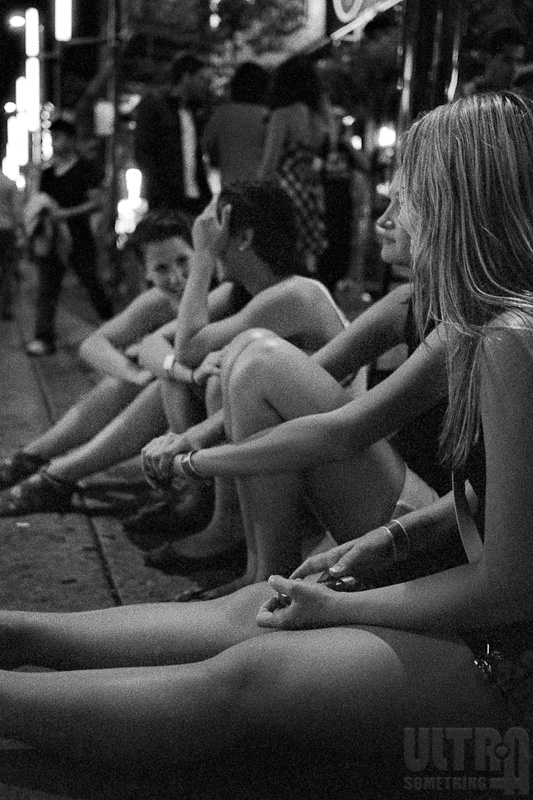

Because our eyes see differently at night, we respond to different stimuli. And, subconsciously, humans alter their behaviour accordingly. At night, we become more aware of motion, angles and shapes. Facial expressions recede into darkness, and we react less to those expressions and more to the language of the body.

A photographer records light and shadow. But night alters the content of that light and shadow, along with the relative significance of each. To force light into the shadowy crevices is to alter the night, not to record it. To use slow shutters and fast lenses to peer into the shadows is to remove the subtlety and poetry of the night vocabulary.

Night has its own geometry, separate and discreet from that of the day. This is why I no longer consider the night to be a challenge of light, but a challenge of subject. My desire is to illuminate the meaning of a scene, not the shadows within it. As a photographer who’s concerned more with documenting life’s moments than with creating them, I’ve come to realize that focus, clarity and sharpness are tools for the day. They help convey the literalness that we, as humans, respond to during the daylight hours. But night is grainy, shadowy, suggestive, mysterious and more open to interpretation. Focus, clarity and sharpness are not necessarily the right tools for a more figurative photography.

I’ve been photographing at night for over twenty years, but until recently I haven’t been photographing the night. Instead I’ve been selecting the same subjects, the same compositions and the same framings I would choose during the day. But as I’ve postulated here, night is not simply a darker version of day; each is utterly unique and should thus be considered on its own merits. It would appear, on occasion, that the assertions of cliché-wielding literary hacks possess credence. Maybe I shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss their banality, but I’m still going to maintain the pointlessness of enigmatic dictionary entries.

About These Photographs: “The Traditionalist,” “Stolen Moment,” “Direction,” “Inspection” and “Synchronicity” were all shot with a Leica M9 and a 28mm Summicron lens. “Nocturnal Classic” was shot with a Leica M9 and a Voigtlander 50mm f/1.1 Nokton lens. “Prelude,” “Lit Up,” “Camouflaged Blonde,” “Camouflaged Brunette” and “Limbs” were all shot with a Leica M6 TTL and a 28mm f/2 Summicron lens using Delta Pro 3200 film, developed 1:4 in Ilfotec DD-X. “Center Line – Granville Street” and “Gravity” were shot with a Leica M6 TTL and a 28mm f/2 Summicron lens using Delta Pro 3200 film, developed 1:9 in Ilfotec DD-X. “Red Light” was shot with a Leica M6 TTL and a Voigtlander 50mm f/1.1 Nokton lens using Delta Pro 3200 film, developed 1:9 in Ilfotec DD-X.

-grEGORy simpson

grEGORy simpson is a professional pounder. You may find him pounding on his computer keyboard, churning out articles for both the Leica Blog and his own blog at photography.ULTRAsomething.com. Or you may hear him pounding on a musical keyboard, composing music and designing new sounds. Frequently, he’s out pounding city pavement and photographing humans simply being. This third act of pummeling has yielded a new photography book, Instinct, which has given Mr. Simpson a fourth vocation — pounding on doors in an attempt to market the darn thing. Follow these and other photographic exploits on the ULTRAsomething Facebook page.

Comments (7)