For many years, I’ve harbored a secret conviction that digital cameras delude us into believing we’re much better photographers than we really are. Snapping up-down and willy-nilly with a blithe disregard for focus, exposure, composition, context, pathos, ethos, irony or significance is a sure-fire way to take a lot of crappy photos. But digital cameras allow us to take so many photos and review them so effortlessly that, inevitably, even the worst photographer manages to accidentally stumble into the occasionally compelling shot. Such cavalier technique works on the “stopped clock is correct twice a day” principle. But with the Delete button so close-at-hand, and without contact sheets to remind us of our failures, we retain only the “good” shots — thus deluding ourselves into believing we’re every bit as wonderful as the legendary photographers who preceded us.

I’ll admit right here — before the eyes of my peers — that I was wrong. To state that digital cameras delude photographers into believing they’re much better than they are is, itself, a deluded idea. Photographers were, in fact, deluded long before digital cameras were but a twinkle in Steve Sasson’s grandfather’s eye. It’s not the technology that deludes us — it’s our own egos.

I stumbled upon this humbling realization on a recent trip down memory lane. “Memory Lane,” as I define it, is “a long strip of acetate with a silver halide coating.” I consider my film cameras to be miniature time capsules. My past self records a person, scene or event that it thinks my future self will find interesting. Some film cameras, like my Leicas, are short-term time capsules — so frequently used that they reveal their images within a day or two after capture. Other, more “casual” cameras (like my medium formats or panoramics), are long-term capsules — often retaining negatives for 6-months before my future self gets to develop them. Curiously, the longer a roll of film sits in a camera, the more convinced I am that Pulitzer-caliber shots reside within. With each month that passes, my future self grows more certain of my past self’s ability to find, frame and shoot moments of sheer magic.

So imagine my delight when, during a recent cleaning expedition into some long forgotten drawers, I found an old Diana camera with half a roll of exposed film inside. I vaguely remember entombing it several years ago, when I decided that the camera (for which I paid a mere $10) wasn’t really worth the cost of the film it shot. I had no idea what kind of film I’d left in the camera, nor any recollection of what those half-dozen exposed frames might contain. I knew only one thing — those exposures sat within the camera for so long that they couldn’t possibly contain anything other than masterpieces!

This discovery set me on another expedition — to see what other film cameras were sitting around with half-exposed rolls. My Widelux, which I last loaded in August, still had a few frames left to shoot. So, too, did my little Rollei 35T. My Yashica Mat was sitting idle on the shelf since December.

These cameras, plus the unearthed Diana, all contained exposures taken by my past self — who my present self has always considered to be a superior photographer. I could barely conceive of the photographic heights I must have achieved within these four rolls of half-exposed film. I could wait no longer. Over the next four days, I took each camera for a walk and exposed its remaining frames, then got on with the task of developing this year’s Oscar Barnack Award winners.

Upon opening both the Diana and the Yashica Mat, I was somewhat surprised to see that each contained Kodak Portra 400NC color film. One thing my present self knows about my past self is that he has practically no interest in color photography. So I’m not completely sure why these cameras both contained color film, nor why I still have several rolls nestled up next to the beer in the bottom of my refrigerator. I suspect my past self got a good deal on some expired stock, and took advantage of it.

When one struggles to make a living with photography, one becomes inherently cheap. So, Pulitzer or no Pulitzer, there was no way I would pay some lab to perform the C41 color processing on this film. Besides, in the past year, all the photo labs had abandoned downtown Vancouver for cheaper rents in the boondocks. I could see no reason to jump in the car, drive out of town, hand over cash money and drive back the next day just to get some color negatives to scan.

So, convinced that my past self had no intention to make any use of the color information contained within this film, I simply stand-developed both rolls of 120 film in Rodinal. During the 60 minutes that the film sat undisturbed within the elixir, I thought about the riches these frames would bring, and of the future assignments that would surely result. After a glorious hour of daydreaming, I gave the film a water stop bath, a swish in the fixer, unspooled the rolls and excitedly held them up to the light. Not a single frame contained the slightest hint of mastery. Each shot was, in fact, as dull and worthless as the bulk of my daily photographic output.

Undaunted, I got on with developing the two 35mm rolls — one from the Widelux and one from the Rollei 35T. In spite of the heightened expectations brought about by my unyielding admiration of my past self, neither strip contained anything of value. So banal were all these shots that, although I’ve sprinkled them throughout this article, I suspect you didn’t even notice them. Masterpieces? Hardly. Noteworthy? Nope. Interesting? Not even. It turns out that, even though my expectations grow exponentially with the amount of time since an image was shot, the shots themselves are no better now now than they were on the day I took them. Delusion is a cruel mistress. She is not the sole province of the digital shooter. She does not distinguish photographers by their chosen imaging surface, lens, camera type or brand. She is merely there, hovering over us — sadistically motivating us to try and live up to our own self-aggrandizing misconceptions.

Which reminds me — I just realized I have a half-exposed roll of film in my Vermeer 6×6 pinhole camera, and I’m rather certain I haven’t shot with it since last autumn. A Post-It™ Note attached to the camera’s top tells me there’s Plus-X film inside but, alas, that note doesn’t tell me what’s on any of the exposed frames. No problem, ’cause I’ll bet you dollars to donuts there’s a Pulitzer Prize sitting on one of those frames…

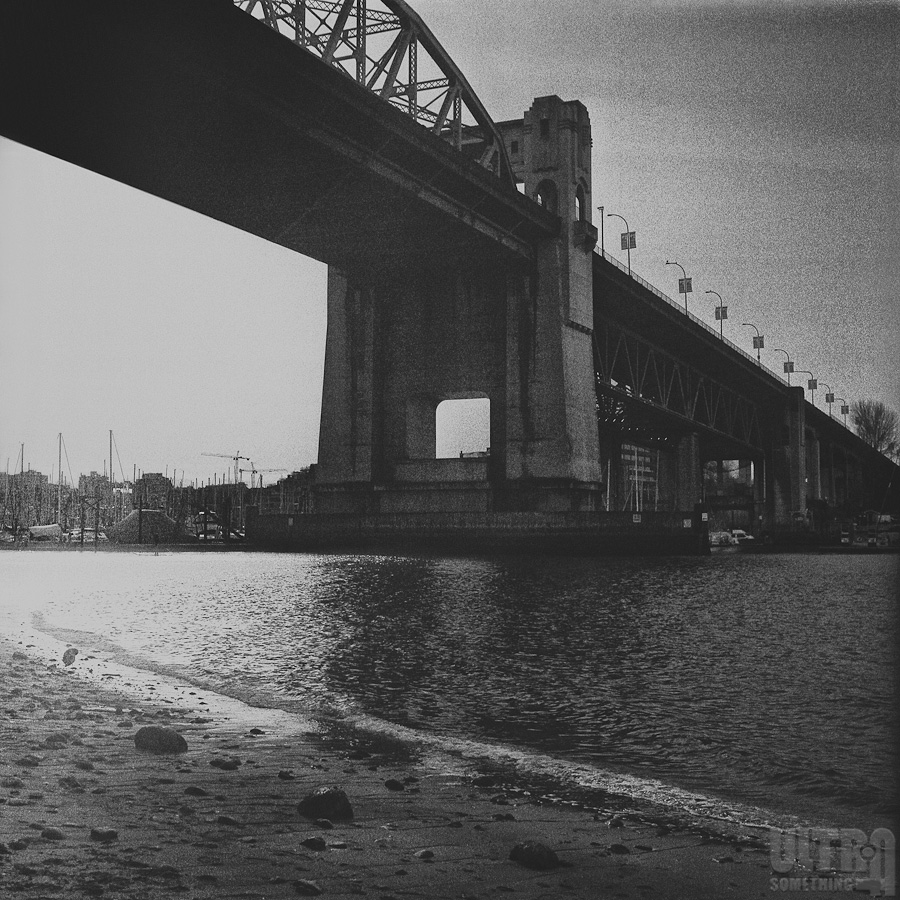

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “Morning, Yaletown” and “Holeyscape” were shot with a Widelux F7 on Tri-X at ISO 400 and developed in Ilfotec DD-X. The first “Rain” and “Shine” set was shot with a Diana toy camera on Portra 400NC at ISO 400 and stand-developed for 1 hour in Rodinal 1:100. The double exposure evident in the sky of the first “Rain” photo is compliments of the Diana’s dicey film transport mechanism. The second “Rain” and “Shine” set was shot with an old Yashica Mat on Portra 400NC at ISO 400 and stand-developed for 1 hour in Rodinal 1:100. “Obfuscated View, English Bay” and “Obfuscated Temptress, Vancouver Sidewalk” were shot with a Rollei 35T on Tri-X at ISO 400 and developed in Rodinal 1:35. Absolutely no Leica cameras were harmed in the writing of this article — I have a whole different set of delusions where those are concerned.

-grEGORy simpson

grEGORy simpson is a professional “pounder.” You may find him pounding on his computer keyboard, churning out articles for both the Leica Blog and his own blog at photography.ULTRAsomething.com. Or you may hear him pounding on a musical keyboard, composing music and designing new sounds. Frequently, he’s out pounding city pavement and photographing humans simply being. And that sound you hear? That’s either the sound of him pounding on doors trying to get hired or, more likely, it’s the sound of him pounding his head against the wall when he doesn’t. Fellow pounders are welcome to follow along on the ULTRAsomething Facebook page or G+ account.

Comments (13)