Mathias Heng is an internationally acclaimed photojournalist who travels the globe with his Leica cameras, frequently covering regions and countries experiencing conflict, war, natural disasters, poverty, social issues, and human struggles. Much of his work is dispassionate in its unflinching directness, but also emotionally charged, a documentary narrative of conflicts and their effects on civilian populations that captures key moments and turning points of human history.

Much sought after as a photojournalist, lecturer and teacher, Heng’s work has been featured such mainstream publications as The Washington Post, The Guardian, The Australian, The Age, and newspapers throughout Asia and Europe. His poignant images also appear in books and magazines worldwide as well as non-government organization publications and journals such as Oxfam USA and Australia, CARE International, Caritas Australia, Australian Volunteers International, AusAID and International Labor Organization (United Nations). He has worked extensively on topical photographic essays in locations including Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, Burma, Cambodia, East Timor, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Kiribati, Mozambique, Nepal, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom and Zimbabwe. In 2000, his images were featured alongside those of other internationally renowned photojournalists such as Sebastiao Salgado in Leica’s product brochure, “The Program.”In 2002, Heng published his first book, sponsored by Leica, Viva Timor Loro S’ae (Long Live East Timor) 1999-2002.

Born in Singapore in 1966, Heng spent 20 years in the UK and Australia, earning his Master’s degree in photography in Melbourne, where he also founded the Leica Gallery, Melbourne. Now based in Singapore, he gives workshops at the Leica Akademie, where he is a source of inspiration to aspiring photojournalists who derive immense benefit from his extensive and unique experiences. In spite of his exposure to many atrocities, Mathias Heng has never lost his passion and commitment to humanity, or his ability to capture images that speak to people around the globe. Here in his own measured and thoughtful words are some of his views on his mission, methods, and motivations.

Q: What cameras and lenses do you use most often in your work, and what is there about them that is especially conducive to your type of photography?

A: I presently use two M-series Leicas, the M6 and M9. I’m looking forward to shooting with The Leica M when it becomes available. At the moment my work camera is the M9 and my favorite working lens is the 35mm f/1.4 Summilux-M. The M9 camera is discreet, small, robust and easy to handle. The 35mm focal length give me a personal perspective because the subjects are aware of me, and there’s no distortion so what you get is honest reporting of what you see with your own eyes.

Q: How would you describe your photography?

A: Reportage and photo documentary.

Q: You’re a photographer full-time, correct? Did you have any formal education in photography?

A: I am a photojournalist full time, and my workshops have also become very popular. As a photojournalist I get invited to do workshops, talks, seminars for public audiences and this has resulted in my receiving more photo assignments and conducting more workshops.

I have always thought of creating images as my calling or profession. I studied photography when I was 14 years old and later pursued my education by earning a Master’s degree in photography. Photographers that I am much influenced by are Eugene Smith, Eugene Richards, and James Nachtwey.

Q: How did you first become interested in Leica and the Leica Akademie?

A: When I first saw images taken by Leica 25 years ago the quality of the results blew my mind away. My involvement with Leica Akademie began in May 2012 and I held my first workshop in July 2012.

Q: What do you enjoy most about teaching Akademie workshops?

A: That by the end of the workshop the participants have learned more about and have a greater appreciation of photography, and even more important, that they are inspired and motivated to put into practice what they have learned.

Q: What approach do you take with your photography or what does photography mean to you?

A: My approach of photography is to approach my subjects with respect and dignity when photographing them, and I do not employ digital alteration. Photography is an essential part of my life, and the topics I cover involve the reality of that life, as I perceive it.

Q. How do you see your mission as a photojournalist that specializes in covering conflict, war, poverty, social issues, and human struggles? Are you striving for literal accuracy in depicting these events in a dispassionate way, or are you primarily expressing their emotional content or some aspects of the human spirit? If it is something else entirely please feel free to express your thoughts.

A: As a photojournalist I am covering the factual aspects of life—the reality of what’s going on. My goals include providing awareness for the public, raising funds to support people in distress, and most importantly to photograph in a way that conveys a deep respect and dignity for the human spirit.

A: The reason I composed and shot those images in that manner was to create the strongest impression while revealing the diversity and complexity of the forms, to present the reality of what I saw in a way that would reach out to the viewer. What do the images means to me? The images mean “life,” and I want my images to speak directly to the viewer. I call this “intimacy,” the fusion of image and viewer.

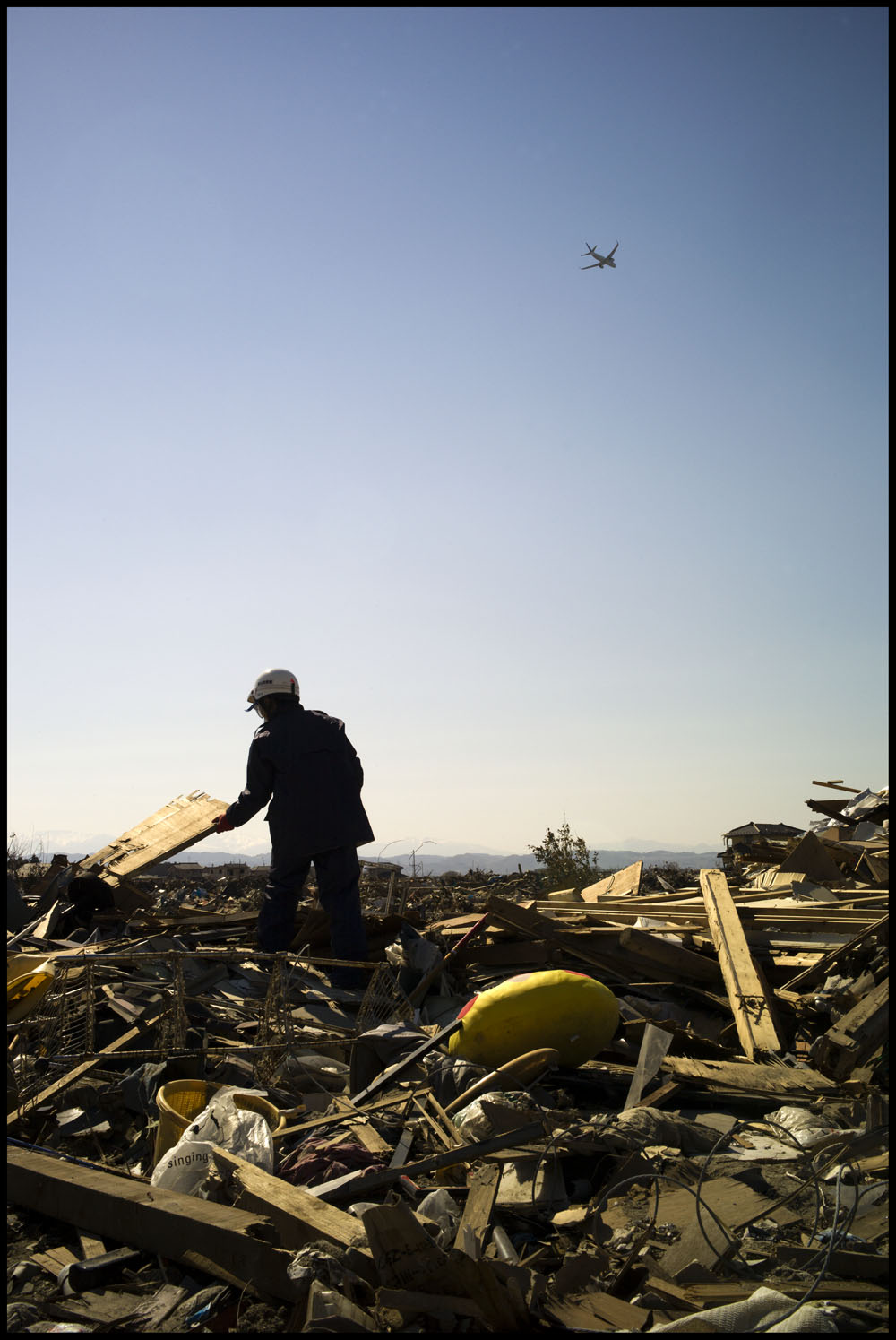

Q: There is one particularly poignant image of a man examining a piece of debris with a jet plane barely visible overhead in the distance—it seems ironic, tragic, and almost surreal. It shows the aftermath of devastation and perhaps cleanup operations. How do you feel about this image?

A: I have been back to Japan 5 times since the Tsunami of 11 March 2011. The workers shown in the bus were in protective suits and masks part of the Fukushima disaster responders. The man with the jet plane in the background was clearing debris and in search of survivors and bodies. It is a strong image for me, for here on the ground, rescue workers are clearing debris and in search of hope for survivors, and up in the sky a commercial plane flies to an unknown destination.

Q: The image of a large ship run aground (L1007472) with a row of telephone poles on the left, a murky gray sky, and a blurred figure in the lower left-hand corner also has a wistful quality, but also an undertone that life persists in the face of adversity. I think many of your images are really about these complex human emotions and in a way the physical reality, however brutal, is just the vehicle for expressing these feelings. Do you agree, and can you share you thoughts on this?

A: Yes, my images they are about life and reality. The ship was pushed inland from sea by the force of the Tsunami and the foreground image is of a postman on a motorbike en route to delivering mails to unaffected homes. It says, in effect, that life goes on.

Q: The picture of men in a bathhouse in murky green light is curious because the structure looks temporary like a tent, not like a typical Japanese bathhouse, which is usually a substantial wooden or masonry building of some kind. It seems to suggest that traditions continue even in the face of cataclysmic events like Fukushima. Am I reading too much into this, and what were you thinking when you shot this picture?

A: The image is of a bathhouse (Onsen) that was set up by the Japan Defense Force, a temporary setup for survivors in Ishinomaki in the devastation area. When I took this image I felt that in times of disaster a simple bath means a lot—it’s one of those basic needs every human needs. Personally I did not have a shower or bath for 7 days while I was on this assignment, so it was something I could relate to.

A: The images you refer to were taken in September 2012. At the time the Japanese people were in the process of re-building their lives after the catastrophe. The group of youngsters was attending a music festival and the image of a lady holding the umbrella was taken in Zao Mountain located in Yamagata, Miyagi prefecture.

Q: Judged alone, the picture of the green and white bus with medical personnel in scrubs, hats and face masks seems very matter-of-fact. However when you think about the image in context it suggests that they’re responding to a disaster, doing what they have to do to help people, and that gives the image a much more heartfelt and emotional character. Do you agree, and what are your thoughts on this?

A: Yes, as I mentioned, these were medical workers, and they were actually going to Fukushima Dailichi Nuclear power plant, which had experienced a meltdown.

Q: How do you inspire and motivate the participants in your Leica Akademie workshops? Are there any helpful techniques or tips you impart that you can share with us? Is there any mindset that is particularly effective in being a successful photojournalist, and is that even something one can teach?

A: My basic teaching method is simply to show my images and share my thoughts as a photojournalist, and most importantly to convey to the participants how I work and how I get my access to my images. To be a successful photojournalist one has to show strong and compelling images if they expect to get your work published.

Q: What are some of your identifiable traits, aside from the passion that drives you to do it, that have helped you to be a consistently successful photojournalist covering some of the world’s most challenging subjects? What do you mean when you say that you have never lost your passion and commitment to humanity despite your exposure to countless atrocities. Why is this a crucial element in your work?

A: In this line of work, getting access is crucial. Most importantly is the “bond of trust” you need to establish in covering the subject—something that must never be abused or compromised. I take my shots with respect and dignity by not setting up my subjects or using a really wide-angle lens to distort them. I have this bond with and love for humanity, and even when the context is war or disaster, I see the positive aspects in people, not just the negative ones. I do get burned out by the end of the day, but I see so much in them, the “so little they have and yet they give so much.” That’s what keeps me going.

Thank you for your time, Mathias!

– Leica Internet Team

To see more of Mathias’ work, visit his website.

Comment (1)